The advent of smart cities has brought with it promises of more efficient, sustainable towns and communities that use data to enhance quality of life for their citizens. City employees have always been tasked with managing public data — building permits, crime records and census data — but the advent of IoT applications brings new, near-constant streams of data coming from city infrastructure. Driven by this data and a desire to remain transparent, many cities have begun maintaining open data portals, where the public can dive into local datasets and request new ones. As the era of generative AI permeates industry, the public sector could benefit from the use of their data portals to support a range of city-specific AI applications, especially to help validate critical green initiatives.

The Take

Dozens of cities across the globe are adding new capabilities to their IT toolbelts as data volumes associated with connected devices and smart infrastructure grow significantly. Publicizing and democratizing access to this data can empower citizens and developers to build their own applications and award city leaders with deeper insight into how their city is functioning and where gaps may exist. Chief data, innovation and information officers will lead their city’s charge into the AI frontier, as stewards over their own massive amounts of local data. Open data portals can empower citizens, lead to more open government practices, facilitate community engagement and validate city initiatives, especially those around sustainability.

Context

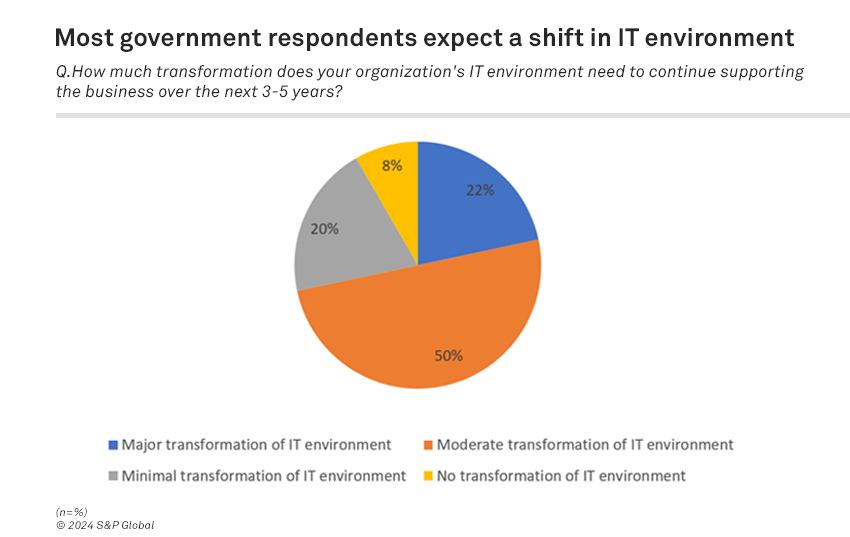

Ensuring data governance processes and infrastructure is up to date will hasten the ability of governments to make the most of their existing data. According to 451 Research’s Cloud Hosting & Managed Services, Cloud Pricing 2022 report, the majority of government respondents (72%) expect a moderate to major change to their IT environment to keep up with business. Just 8% expect that no change will be required to their legacy cloud, server and IT infrastructure in the next three to five years.

Governments have been looking to make data available online since the early 2000s. Early efforts in open data include the US’ data.gov site, first published/launched in 2009, and the UK’s uk.data.gov site in 2010. Both sites aimed to promote transparency and make city data accessible. Other city data efforts followed, including Kenya’s Open Data Initiative, India’s data.gov.in and Open Data Philippines. Looking to provide a global forum for open government collaboration, the Open Government Partnership was founded in 2011. The partnership now counts representatives from 76 countries and 106 local governments among its members.

The data that feeds these portals varies greatly. Most cities organize their data according to city priorities or vertical industry, with common categories including public safety, sustainability, economic indicator, quality of life/social and others. Individual data sets can range from business permits licensed, housing occupancy status, ground water supply or municipal carbon-neutrality progress. Data is uploaded via an API using ETL applications on predefined schedules, or inputted manually.

Portals

Open data portals vary in their purview and delivery format. The majority of cities, including Charlotte, NC; Glendale, Ariz.; and Washington, DC, make their data available via ArcGIS, a geospatial platform provided by Esri. ArcGIS offers benefits in visualization capabilities, integration with existing data infrastructure and interoperability of data in various formats — maps, web applications and services. One tool that users can take advantage of is layered datasets. Users can overlay air-quality data over socioeconomic indicators, for example, to identify where an air-quality monitoring pilot may make the biggest impact on citizens. Other cities publish their data with visualizations or data stories for ease of use and transparency for citizens. Other vendors in the segment include Tyler Technologies Inc., Socrata and Junar. Open data portal examples include the following:

- London: The London Datastore, managed by the Greater London Authority, first launched in 2010. The data store collects datasets from hundreds of endpoints to populate a citizen-facing analytics dashboard. Complete with 1,124 data sets across over a dozen indicators, Londoners can visualize economic indicators like unemployment by sector, transportation insight on number of transit journeys and reliability, and environmental metrics like PM2.5 concentration and domestic energy-efficiency ratings. This data is ingested via API from a host of partners, including Clarity.

- Reykjavik, Iceland: Iceland’s capital city hosts an open-source data buffet, complete with 572 datasets. The city uploads data via the comprehensive knowledge archive network API, which facilitates the creation and management of open data portals for public sector agencies. City leaders have prioritized making data visually appealing and accessible for citizens to interact with. Data is packaged and aligned with policy areas, including transportation, sustainability, citizen welfare and education.

- Cincinnati: Cincinnati’s Open Data Portal was conceived from a 2015 plan by the city manager to deliver innovative government. With 158 datasets, the city ingests some data daily, like car crashes, and others on a weekly or monthly basis, like employee payroll. Citizens of the city can find data sets on safety, economic opportunities, neighborhood-level insight and fiscal sustainability. Beyond ingesting data via API, chief data officer Cameron Wilson says that de-identified data is loaded and processed into a portal hosted by Socrata, a data visualization platform for governments. Most popular datasets include police and crime data for the city’s safe streets plan; the most common users are often community council members, who use the data to generate reports.

City impact

Open data portals can have meaningful impact across city operations, from enhancing transparency to validating initiatives around sustainability and emissions. This data can be used in city-led hackathons to promote application development. Cities may also work with vendors to create chatbots that are trained on city data to answer questions and automate manual processes.

Sustainability: Government leaders across multiple levels, from local to federal, are at the forefront of their municipalities’ efforts to reach sustainability goals. The C40, for example, is a network of 96 global mayors dedicated to halving their city’s overall emissions by 2030. The initiative hosts several “networks,” including municipal building energy efficiency, cool cities, water security and more. Each network focuses on outlining technology and implementation strategies to achieve a sustainability goal. IoT devices, including air- and water-quality sensors, can play an instrumental role in providing the data cities need to validate their sustainability initiatives. By determining a baseline and monitoring air and water quality on an ongoing basis, city leaders can gain up-to-date insight on how their carbon reduction efforts are progressing. The city of Denver, for example, has installed hyperlocal air-quality sensors at local schools to collect and report on air quality on a daily basis. Other metrics, like urban tree canopy, collected via satellite imagery, can help decision-makers prioritize new builds in an area where tree cover is minimally affected to help reduce urban heat islands.

AI application development: The public sector can tap into its vast amounts of data to make use of community- or citizen-led application development. City-specific data lakes, or open data portals, could serve as a central repository from which city leaders and community members could build applications.

- Community-led application development: A common route to community engagement is in hosting open data hackathons, where local developers can hack open data to build a new application or solve a city problem. The annual Nordic Open Data Hackathon invites participants to use existing open data sets to build AI applications that align with the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals. Participants were given road camera, weather, air-quality and traffic data available via API to build an application, and the winning entry built a routing software platform. Cincinnati has a similar hackathon focused on using open data to optimize recycling efficacy for citizens.

- City-led chatbots: Many cities are turning to rules-based or AI-powered chatbots to automate services and provide city information in multiple languages. Upon visiting Los Angeles’ city website, users are greeted by CHIP, the city’s virtual assistant bot powered by Microsoft Corp. Citizens can input requests about air quality, trash collection schedules and upcoming events. Chatbots are trained using textual data from city websites, frequently asked questions, public transit schedules, city services and events, geospatial data, and user feedback. While some are simply rules-based, cities are looking to AI-powered or generative AI chatbots that can create new content, provide multilingual support and scale as demand increases. The city of Austin, Texas, also has four chatbots, and is looking toward generative AI capabilities to enhance information delivery for citizens.

As cities get more familiar with their own data, and set up data governance and sharing processes both internally and externally/regionally, open data portals can serve as a jumping-off point for more extensive projects.

Want insights on IoT trends delivered to your inbox? Join the 451 Alliance.