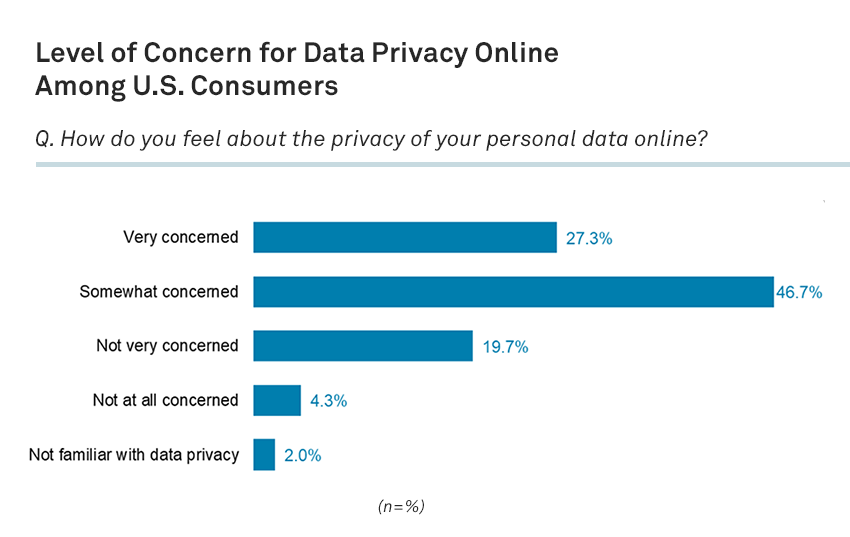

Consumers today care about data privacy and security online, particularly in the US. While this awareness can be beneficial in prompting consumers to advocate for themselves, it can also make them susceptible to sensational reporting and word choices that potentially misconstrue events in information security.

While editorial or journalistic choices to emphasize corporate “breaches” and “leaks” make for clickable headlines that place the blame on shadowy parties ostensibly stealing our personal data, the more complex reality is that there is no lack of digital-first businesses that operate in an ethical gray zone — collecting and exchanging data for profit that is not fully protected by existing regulations. What may be initially reported as a “leak” may simply be inaccurate reporting of a business practice that was disclosed deep in the terms of service.

This is especially true in the US market for healthcare-adjacent data, where HIPAA (signed into law in 1996) protects only clinical records and other certain types of official medical data. HIPAA was never designed to foresee the omnipresence of cloud architecture, the availability of wearable technology or the prevalence of direct-to-consumer health apps. Digital businesses that operate in this realm are often able to collect data directly pertaining to personal health that is not strictly protected by regulation, treating it much as they might treat any other personally identifiable information, without increased sensitivity.

These business models, especially for free or freemium services, often depend on the sale and exchange of data that the consumer may not be reasonably aware of. It is not uncommon for these quasi-legal data sharing arrangements to be “exposed” and subsequently — rather, inaccurately — reported as breaches or leaks by the press, further confusing consumers.

In early 2023, the Federal Trade Commission in the US took aim at a popular prescription coupon/discount app for the sharing of consumers’ health data with third parties for advertising purposes. In the mainstream press, this was initially often reported as a “leak” of data. However, deeper analysis would suggest that this was in fact part of the company’s ongoing business strategy, even disclosed in the application’s terms of service as it was updated. Selling and sharing data often is not a leak or breach; it is a persistent revenue model permitted by ambiguity in existing regulation.

Yet journalistic choices in reporting these matters can further confuse and misdirect the anger of consumers. Not only do we need clearer and more concise reporting on information security, we also likely need clearer regulatory language and stronger enforcement mechanisms. No single consumer should be expected to overhaul the economic profit model of online services. However, consumers likely do deserve to be better informed, even if they may not have the time or skills to read the constantly evolving terms of service for every application they use.

Want insights on Infosec trends delivered to your inbox? Join the 451 Alliance.